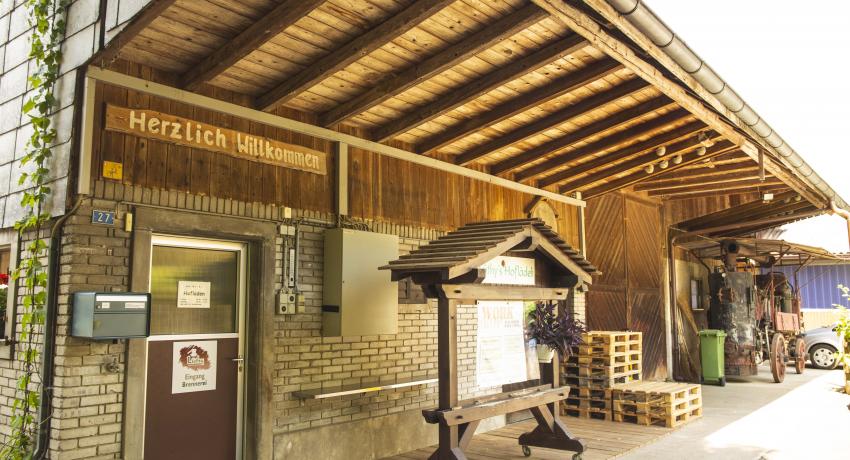

Visitors to Lüthy distillery in Canton Aargau, Switzerland, are greeted by the sight of the 1920s, wood-fired, mobile still at the front. You might be forgiven for thinking that Lüthy Distillery is that - it’s not, but it used to be. A portable distillery was not an uncommon sight in Switzerland, I saw one outside a farm one day while it was making apple schnaps - the idea being that in a good year the farmers would call the distillery who would roll up and transform whatever surplus crops there were - apples, pears, cherries, plums and what have you - into something drinkable. But not whisky, as Urs Lüthy explained to me:

Up until 1999 it was illegal to distil starchy staple foods - barley, other cereals or potatoes - due to a 1930s law to combat food shortages that was never repealed. So if anyone offers you a Swiss whisky (there are about 50 Swiss distilleries making whisky at the moment) that is more than 20 years old, there might be something wrong with it.

When he took over the farm, Urs decided that he needed to diversify, like many farmers today. This wasn’t such good news for the cows, who had to leave to make room for the stills. The story recalls the early days of the Scottish and Irish distilling industry, when farms that sidelined in whisky were the norm rather than the exception that they are today. Ballykeefe in Ireland and Kilchoman in Scotland are farm distilleries, while many others started off as farms and later evolved into full-time, legal distilleries.

Lüthy’s production water comes from the mains, and that is the only ingredient that is outsourced.This is very much a ‘grain to glass’ distillery - Urs harvests all his own grain, malts, mashes, ferments, distils, matures, cuts and bottles everything here. He tells me that the barley is harvested already; the corn is still waiting in the flat fields outside that were once part of a large Roman estate in the area.

Urs malts his barley on a shed floor, turning it with a wooden spade in the old ‘monkey shoulder’-inducing style (maltmen tended to have one shoulder bigger than the other after a few years). Mashing and fermenting is done in stainless-steel vessels, and Urs double distils in German Schnaps stills. The stills, 100, 180, and 2 x 250 litres, were made by Holstein of Lake Constance - West Cork Distillery has a couple by the same maker. Though these stills were designed to make fruit alcohol (where the spirit evaporates and condenses many times on its journey upwards), by opening the valves inside the columns Urs can operate them like traditional pot stills.

Maturation is done down the lane in an airy, dunnage-style warehouse but without the natural floor. The spirit lost to evaporation, the angels’ share, is a fairly high 5% here compared to the Scottish 2%, especially today when the internal temperature is somewhere in the low twenties. The whisky is aged in an impressive array of different casks – ex-bourbon, sherry, wine, and ex-whisky casks such as Bowmore and Laphroaig that will lend a smoky nuance to the whisky, all to be sold in special-release batches.

Urs seems to like to try his hand at everything, like his ‘bourbon-style’ whisky, made with maize and barley, craftily called ‘Böörbon’. He also makes a very tasty rye, spelt (a first for me), and even a rice malt whisky (another first for me - Swiss law places no restrictions on the raw materials, so long as it is a cereal, and rice is one after all). A couple of years ago they helicoptered his other, more modern (even if it doesn’t look it), wood-fired, mobile still onto the Titlis mountain and distilled what was presumably the highest-ever distilled whisky - named ‘3020’ after the altitude.

Filling about 10-25 casks a year, Urs seems remarkably relaxed since he is the only employee at Lüthy distillery - and come to think of it, it’s fairly apt then that the whisky he sells is called ‘Herr Lüthy’. It is still a working farm, by the way, and this is the only distillery I know where you can buy fresh fruit, fresh veg, fresh eggs and fresh whisky all in one go.