- Log in to post comments

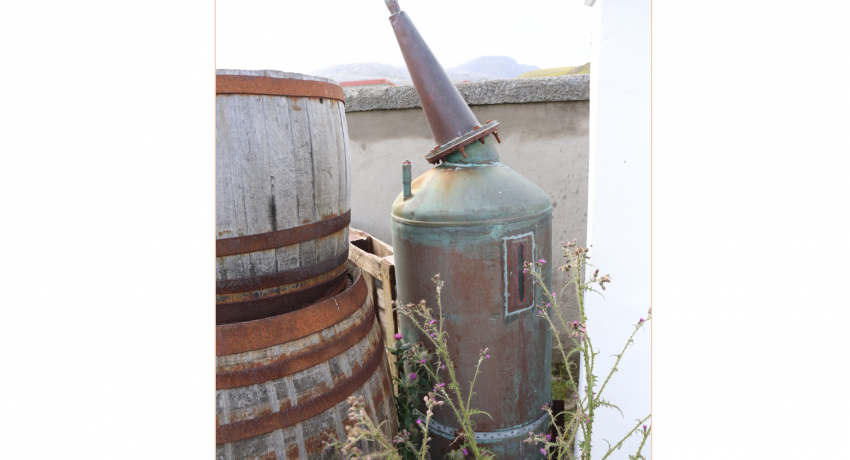

First impressions count – or maybe not. As I arrive, it looks like I have taken a wrong turning into a builder’s yard and I am half tempted to turn back. Pipes and bricks lie scattered around, a cement mixer there, a plastic crate here. An electric van sits charging itself from an extension lead coming out of an open window. There’s little at first sight to suggest a distillery to my mind, besides the few barrels at the car park near the road – until, at the gate, I spot a small still sitting as if abandoned, like the ones that would once have been used to make illicit whisky.

In common with most visitors, I missed the entrance first time around and carried on the road a few miles until it came to a stop near some of the most stunning beaches I’ve ever seen - great if you get the weather for it, which is not the case today. But on closer inspection, the barrels act as the signpost for the distillery, next to large wooden replicas of the Uig Chessmen, ivory chess pieces dating back to the 12th century, found in a sandbank near here in 1831, now divided between the British Museum and the National Museum of Scotland.

I meet a family from Germany also waiting when I eventually decide that I have found the distillery. They say they have seen someone hanging around already, and he told them that the tour guide will be along shortly. The said guide does arrive after a few minutes and she opens up one of the sheds, which has a bar and a few tables where unlabelled bottles and demijohns half full of whisky have been left as if in the middle of a makeshift filling session. Joanie is the tour guide, secretary, bottler, labeller and general odd jobber at Abhainn Dearg (Pron. Avven Jearg). The tour was supposed to start at 11, but she says she’ll wait a few minutes, to give those who have missed the entrance a chance to arrive. Like I said, most visitors …

Sure enough, a couple from Glasgow turn up before long and ask if they are still in time to join the group. I mention to Joanie that I had sent a couple of emails asking if I could book a visit. ‘Oh, I check the emails about once or twice a year’ she says. That would explain why I didn’t get a reply, and I think I like this place already.

The story behind Abhainn Dearg is a simple enough one. Marko Tayburn, a builder from Stornaway, decided that he would like to start making whisky. Fair enough. He found the ideal site, put in the stills, and started distilling - learning the craft as he went along. That was just short of ten years ago, and the business is going from strength to strength. His first ten-year-old single malt is due to be released later this year.

Joannie starts off by showing us the on-site maltings and mentions that the barley they use is grown on the island. I’ve seen a few maltings, and let me tell you this is a far cry from Port Ellen and Glen Ord. At Abhainn Deargh, in a plastic crate in the yard, a few bags of Concerto barley are soaked and left to germinate. Once sprouted, the grains are transferred into a tray in one of the sheds that sits on a grid above a small cast-iron stove fired with local peat. The chimney is blocked off and the smoke is left to permeate the grains for two days, before being air dried to complete the process, resulting in an original phenol content of somewhere short of 30 ppm, something like a Bowmore.

In the main production shed, stainless steel mash tuns feed 7,500-litre Douglas fir washbacks that ferment the wash for 4-5 days until the alcohol reaches 5-6%. Cooling and mashing water comes from the Abhainn Dearg, the ‘red river’ that flows past the distillery - named a bloody battle that was fought between the locals and the taxmen in ages past. There is history between the two, then. This used to be smuggler country, and although Ahbainn Dearg are making the first legal whisky in the Outer Hebrides in nearly 200 years, the spirit has probably never really ceased to flow in all that time. The river also provides electricity through a water turbine to heat the boiler and power the distillery, not to mention the electric van. This must be as close to carbon neutral as distilling gets.

At the other end of the shed, two ‘hill’ stills sit on a raised level with traditional (marvellous) wooden worm tubs, that cool the distilled steam back to liquid through coiled copper pipes submerged in cold water. I’ve never seen hill stills like these before - except for that small one a few minutes ago out at the gate, of course. I think hill refers to the place you would normally find them hidden. These two larger versions seem to have been large water boilers in the past, with conical still heads and thin lyne arms welded on top, copied from the design of the smaller one outside. Interesting, and isn’t it tempting to think that the whisky will taste something like the old smuggler whisky?

Abhainn Dearg is a grain-to-glass distillery, and so everything is matured on site in a bonded warehouse. It is filling up fast, and plans are already in place to build another warehouse. Casks from the Speyside Cooperage are mainly ex-Bourbon and PX sherry, with some as yet unreleased wine casks. Production is currently around 5,000 litres a year, which translates as 10,000 of those half-litre bottles that Joanie has to fill and label at the on-site bottling plant - the table with the demijohns in the visitors’ centre. At present the vanilla and gingery single malt of about four years is available, matured in ex-bourbon, 46%, and a fruity, sweet ‘spirit’ that doesn’t have the three years to let them call it whisky, also 46%. (Abhainn Dearg's first 10-year-old single malt was due to be released in 2018 after my visit, and I haven't tried it yet.)

Owner Marko Tayburn comes along to have a chat. He is a no-nonsense, well-built fellow, and looks like carrying a hod-full of bricks up a ladder would be no bother to him. I ask him what prompted him to start a distillery, and he gives me a vague enough answer that suggests it simply seemed like a good idea at the time. He bought the site because the buildings had been used as a fish hatchery, and so technically the permissions to make whisky were already in place, helping to bypass a lot of the paperwork. When I ask what his experience of the whisky industry was before Abhainn Dearg, he says that he can’t really answer that question - which is actually one of the best answers I have ever had to that question.

Marko works here with three or four others on the production side of things, with Joanie and another on administration, besides the farmers and other jobs that have been created by the distillery. Like Marko, Abhainn Dearg is also very much a no-nonsense, take-us-as-you-find-us distillery (or if you find us even). It may not be as pretty as the Strathislas and Laphroaigs of this whisky world, it may not have the history of the likes of Macallan, well, not yet, and doesn’t boast the panache of Glenmorangie and probably never will, but in its own way Abhainn Deargh has as much character and individuality as any one of them. Let’s hope the whisky has too.